“Women and non-white individuals did not have access to as many educational opportunities or ensembles to play their music. That’s why there is not much significant music written by those individuals before the twentieth century.”

I have heard some variation of that argument countless times in my twenty years as a professional musician. Perhaps if I were not an avid scholar and performer of music by under-represented seventeenth and eighteenth-century composers, I too would have fallen prey to the fallacy that women and non-white composers were not writing so-called “art” music during the common practice era.

After all, it *is* true that literacy rates among women and non-white individuals were often significantly lower than those of white men in many regions of Western Europe and North America for centuries. Not to mention the catastrophic amount of intellectual and creative genius that was suppressed via the dehumanizing atrocities of slavery and its lingering systemic inequities.

Whether blatantly intentional or not, the field of classical music has, in fact, bequeathed a select few white men with nearly god-like status in the canon, giving the illusion that no one else was writing music of equal merit or value.

Despite these prevailing misconceptions, and frankly, in spite of having the odds often stacked against them, women and BIPoC composers were writing music throughout the common practice era.

Not only were these individuals writing music, they were writing a lot of music, and much of it was (in my opinion) quite good! In some instances, women and non-white composers were substantially more prolific than their male contemporaries. Barbara Strozzi, for example, published eight volumes of her own music before her death in 1677. Not only was she one of the most prolific composers of her time, she is also credited with creating the cantata genre. She accomplished all of this without the patronage of either a court or the church. Her music is not included in any mainstream theory textbooks. Similarly, Joseph Bologne was a contemporary of Mozart and wrote countless pieces in all of the same genres and styles. Yet today, Mozart is a common household name of the aforementioned ‘god-like’ canonical status, and until recently, most references to Bologne pejoratively referred to him as “Black Mozart.” I really like Mozart’s music, but Bologne’s is also quite excellent.

The sentiment that women and non-white individuals were not composing music (or music of “value”) during the common practice era is blatantly apparent in the undergraduate theory textbooks used in U.S. college, university, and conservatory curricula.

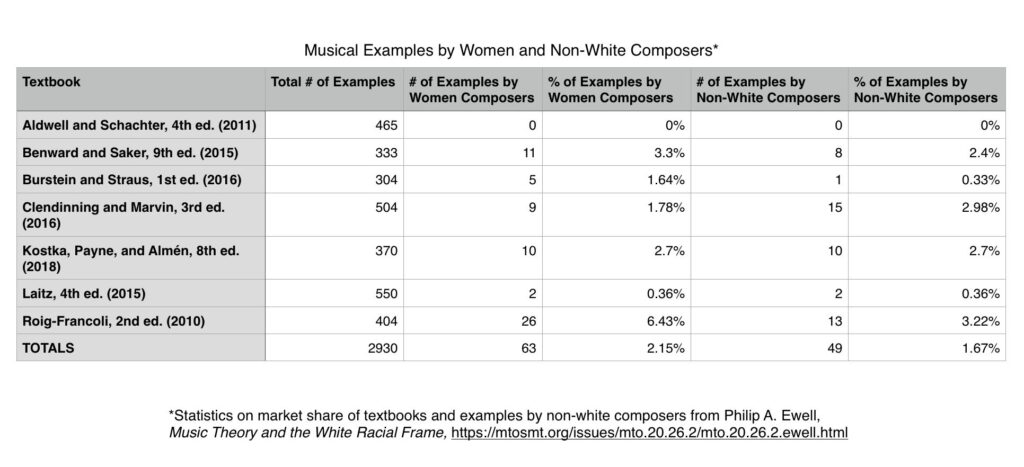

Phillip A. Ewell has calculated that there are 2,930 musical examples in the 7 most-used undergraduate music theory textbooks in the U.S.

Of those examples, 1.67% are by non-white composers, and by my calculations, just 2.15% are by women.

At present, there are several hundred examples on this website from 32 composers. These examples represent only a fraction of the common-practice-era music by women and non-white composers.

The discipline of music theory must continue to reconcile with the inherent racism and sexism that exist at the very core of the field. In the meantime, the least we can do as educators is expand the canon of composers we teach in our classrooms.

Bravo, Paula, for taking on this important, Herculean task. It is a good idea to bring these forgotten composers and their music to the light of day. I would be curious to know what your students’ reaction is to these new sources. Good luck to you in these endeavors.

Thanks! So much of my theory teaching inspiration came from your courses! My students are really fantastic, and they have been very open to and excited to study music by these composers.

Excellent work Paula! This is a great resource that I’ll use and cite often…well done! I’m glad that my work has intersected with yours.

Thanks for the tremendous amount of work you have done to get these critical conversations started in our field!